Kentucky flooding raises urgent questions about Appalachia’s future

[ad_1]

JACKSON, Ky. — Teresa Watkins worked to salvage a few mud-caked belongings from her home on a Breathitt County branch of the Kentucky River after July 28 floods slammed her neighborhood for the second time in 17 months.

The 54-year-old, who has lived off Quicksand Road since she was a teenager, said the flooding in recent years – “more and more, worse and worse” – has left difficult dilemmas in a county where median household incomes of $29,538 are less than half the national average.

She pointed to a mobile home one family abandoned last year. Now, more say they’re leaving for safer areas, she said, but it’s not that easy.

“I don’t know how they can afford it, or where they’re going to go. Any property is basically along the river line or creek banks,” she said. “And if they go up on the mountains, the mountains slide.”

‘I CAN’T GET OUT’:As historic flooding raged, Kentucky woman survived by binding herself to her kids with vacuum cord

Devastating floods that killed at least 37 people in Kentucky and recent damage in other parts of Appalachia, including Virginia and West Virginia, are fueling urgent questions about how to mitigate the impact of hazardous flooding that is only expected to increase as climate change fuels more extreme weather.

But in one of America’s most economically depressed regions, there are few easy answers.

The region’s mountainous landscape, high poverty rates, dispersed housing in remote valleys, coal-mining scarred mountains that accelerate floods and under-resourced local governments all make solutions extremely difficult.

Measures such as flood wells, drainage systems or raising homes are expensive for cash-strapped counties. Buyouts or building restrictions are difficult in areas where safer options and new home construction are limited. Many are unable or unwilling to uproot.

And tamping down extreme weather by reducing climate-changing emissions nationwide is a goal that is politically fraught, including in a region with coal in its veins, that promises no quick relief.

“If we had all the money in the world, and we had the political will and cooperation, we could go a long way towards solving these problems,” said William Haneberg, director of the Kentucky Geological Survey and a professor of Earth & Environmental Sciences at the University of Kentucky.

Even as Kentucky’s devastation renews attention to longstanding challenges, some residents say they have little hope that effective protections will arrive anytime soon.

For now, the emphasis is on trying to rebuild what was lost. In Kentucky, Gov. Andy Beshear said recently that he may call a special legislative session for more aid to the region, and FEMA is providing housing and other help.

CLIMATE POINT:Subscribe to USA TODAY’s free weekly newsletter on climate change, the environment and the weather

Still, repeat floods have prompted some officials to search for longer-term answers. Buchanan County, Virginia, for example, is drawing up a flood-resiliency plan to identify projects to blunt flooding’s impact. But those projects would still have to be paid for.

Some residents are fatalistic or doubt the government can do much. Others are pushing for more protections in areas where many have few options to move and can’t afford flood insurance.

In the Buchanan County community of Pilgrim’s Knob, Sherry Honaker, 55, this week watched crews remove debris from her niece’s home on Dismal Creek. It was gutted in a major flood about two weeks before the Kentucky floods – the county’s second this year.

“Something needs to be done,” she said.

How susceptible is Appalachia?

Central Appalachia is no stranger to flooding. But the latest high water in Eastern Kentucky was record-breaking, and experts expect more to follow.

Amid the larger pattern of extreme weather in the United States, from wildfires to heat waves, meteorologists and climate scientists say human-driven climate change comes with a warmer atmosphere capable of holding more moisture.

That can mean more bouts of intense rainfall, and more rain in a short period of time fuels flash flooding, said Antonia Sebastian, an assistant professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill specializing in flood resilience and mitigation.

The region’s topography also contributes to how “flashy” a flood can be, Sebastian said.

The steep slopes of the Appalachians allow water to rush quickly into the narrow valleys below, sometimes swamping hollows before residents have a chance to escape.

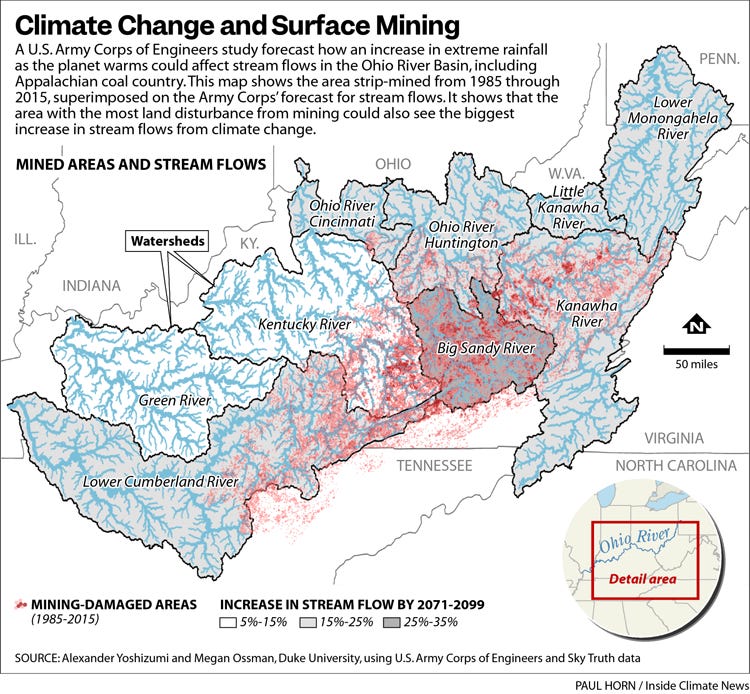

In 2019, an Inside Climate News analysis of U.S. Army Corps of Engineers streamflow data and satellite images of disturbed land from strip mining found areas such as the Big Sandy watershed, which straddles the Kentucky and West Virginia state line, to be among the most threatened by climate-change-fueled extreme weather within the Ohio River Basin.

The region’s history of coal mining, as well as logging, can exacerbate flooding, experts said, by dramatically altering the landscape.

With surface mining, trees are the first to go, then sometimes hundreds of feet of rock are blasted away from the tops and sides of mountains to get at underground seams of coal.

“Normally, on a forested hillside, the trees and their roots will absorb 40% to 50% of the rain that falls, then slowly release it,” said Jack Spadaro, a former top federal mine safety engineer. After mining, surfaces robbed of vegetation help fuel flash flooding, he said.

INFLATION REDUCTION ACT:What you need to know about major effort to fight climate change

Housing patterns also contribute to the area’s vulnerability, with many residences scattered in smaller communities along a road that often winds along a creek lined with steep hillsides.

In Kentucky’s Breathitt County, for example, half of all homes are at a high risk of flooding, according to data provided to USA TODAY by the First Street Foundation, a research and technology nonprofit that tracks flood risks.

The same is true of 46% of homes in Perry County and 58% in Letcher County.

“You hear people say, ‘Oh, you know, they shouldn’t live in a floodplain. They should move someplace else.’ But if you look at a lot of these towns, there are really not a lot of good options,” Haneberg said.

Added to that is the area’s economic vulnerability. Many residents cannot afford flood insurance.

Amid coal’s decline, good jobs are hard to find. Breathitt County’s poverty rate is 28%, more than twice the national rate of 11%. The median home value of $53,000 is less than a quarter of the national average, according to the U.S. Census.

The region has higher rates of chronic disease and populations that have fallen in recent decades.

Jessica Willett, 34, whose remote Jackson home was pushed downstream by flooding while she and her two children were inside, said she was nervous about rebuilding on Bowling Creek.

But it’s also a home she doesn’t want to leave.

“My aunt down the road, she is going to move. She lost everything,” she said. “It’s just hard because down here, there’s a lot of family land. We want our kids and grandkids to grow up on it.”

The ‘pain points’ of climate change

Standing near Dismal Creek in Virginia, Honaker looked over a giant pile of rubble. She said she wants officials to ramp up unclogging draining culverts or increasing the creek’s depth.

She looked at her niece’s home: “Maybe stilts would have helped,” she said.

While it’s impossible to halt heavy rains and flooding, counties and towns can consider measures to limit their impact, said Tee Clarkson, a principal at First Earth 2030, a company helping Buchanan County develop its flood resiliency plan.

That could include flood walls, strengthening creek banks, dredging creeks to greater depths and expanding piping and drainage systems, he and others said. Houses could also be raised on stilts.

“It’s hard to keep areas from flooding, but you want to lower the pain points” for residents and infrastructure, he said.

U.S. Rep. Hal Rogers, who represents Eastern Kentucky, said in an area with a “long and daunting history of flooding,” he’s helped secure more than $800 million over 40 years to help build flood walls, levees, tunnels and other public safety projects.

“However, this flash flood was a natural disaster that turned small creeks and mountain run-off into raging rivers that chartered a new destructive course through our valleys and hollows,” he said. “These types of floods have always been one of the greatest challenges to mitigate in the mountains, and I will continue to advocate for every possible resource that we can afford to protect our mountain communities.”

‘NET ZERO?’ ‘CARBON NEUTRAL?’ Climate change jargon got you confused? Let us explain.

What could also help, experts say, is tackling the hundreds of thousands of acres of former mine land in Appalachia still to be reclaimed, according to a 2021 report by the environmental group Appalachian Voice.

Counties can also restrict building or add stricter building requirements, but that is easiest for new construction – in places like Perry County, Kentucky, few new building permits were issued in recent years, according to the U.S. Census.

Perry County Judge-Executive Scott Alexander said he’s looking for ways to make his county more flood-resilient, such as raising bridges or expanding reservoirs. He said a future discussion might include raising homes in flood-prone areas.

“We’ve got to start looking at preventive flooding measures,” he said. But he cautioned that “when you get to 12 inches of rain, especially in Appalachia, there’s not a whole lot of anything that can handle that.”

Federal Emergency Management Agency buyouts have been an option, but they take time and can be fraught with potential harm, Sebastian said. The Central Appalachian population is one of the poorest in the country and moving that population out of a region with a generally low cost of living could bring further economic hardship.

And the properties in the most flood-prone areas tend to be the most affordable, further endangering the very poorest Appalachians, said Colette Easter, president of Kentucky’s section of the American Society of Civil Engineers.

“That involves gut-wrenching questions about moving away from a place that you’ve lived for a very long time, maybe generations, and you’re very connected to,” Eric Dixon, a researcher at the Ohio River Valley Institute, said with a deep sigh. “But maybe you don’t have another choice. Maybe that’s literally what you have to do. That’s the real heartbreaking part of this, I think.”

Flooded residents, difficult choices

For 15 years, Angie Rosser has lived along the Elk River in Clay County, West Virginia.

In 2016, a powerful flood hit the state, killing 23 people and causing more than $1 billion in damage.

Six years later, Rosser said her community still doesn’t have a grocery store. She hasn’t replaced much of the furniture she lost. In Rosser’s house today, you’ll find a bed, but no couch and no dining table.

“My house is pretty empty, because I am expecting another flood to happen – which is not a great way to live,” said Rosser, the executive director of the West Virginia Rivers Coalition.

Rosser understands the commitment to stay and rebuild shared by many of her neighbors, but “I’m not one of those people,” she said. “If it floods again, I’m out. I can’t do it again. It was just too exhausting.”

That same weary uncertainty has spread across hard-hit counties in Kentucky this week, where the next disaster lurks behind each heavy rainfall to come.

IS THE GLOBE PREPARED? Extreme heat waves may be our new normal, thanks to climate change.

VISUAL EXPLAINER:One graphic shows why Biden says executive actions on climate change are needed

Dee Davis was a Hazard, Kentucky, kindergartener when a flood devastated the area in 1957. It is seared into his memory. He recalls his grandmother and great-uncle taking a canoe to buy groceries.

“We lost everything,” he said.

That flood 65 years ago set a record water level for the North Fork Kentucky River, at 14.7 feet in Whitesburg. Locals never forgot the damage it wrought.

The most recent flooding put that same river at about 21 feet. The water rushed in with enough force to destroy the U.S. Geological Survey sensor designed to monitor the water level.

On Whitesburg’s Main Street this week, the stuffy odor of mud lingered everywhere. The sidewalks were littered with growing piles of discarded furniture, rubble and children’s toys.

For now, the path ahead starts by reckoning with what was lost.

“You mourn the dead,” Davis said, “and you find a way to go forward.”

James Bruggers is a reporter for Inside Climate News.

Contact USA TODAY national reporter Chris Kenning at [email protected]

[ad_2]

Read Nore:Kentucky flooding raises urgent questions about Appalachia’s future